Our genetic code may determine whether or not we have a sweet tooth, a new study has found. Researchers noted an association between people who consumed high levels of sweets and one variation of a hormone.

Animal studies have suggested that a hormone produced in the liver regulates sugary food and drink consumption. Researchers further explored this link between biology and behavior and found that a preference for sweets may have a genetic underpinning (Cell Metabolism, May 2, 2017).

Matthew P. Gillum, PhD

Matthew P. Gillum, PhD"The A-allele is a common variant in the FGF21 gene that is associated with increased sugar intake and sweet snacking in humans," Matthew P. Gillum, PhD, co-senior author of the study, told DrBicuspid.com. "We were interested in doing these studies because of ... [prior] studies showing that this variant is associated with changes in macronutrient intake in humans ... and also because of studies we had done in mice that showed FGF21 suppresses sweet intake."

Gillum is an assistant professor at the University of Copenhagen and a member of the university’s Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research.

Sweet tooth driven by hormones

As the scientific and health communities learn more about the role nutrition plays in oral and overall health, there is also more of a desire to understand biological mechanisms that affect diet preferences. Previous studies have suggested that the hormone FGF21, short for hepatokine fibroblast growth factor 21, may regulate sugar consumption. The researchers, therefore, decided to further investigate the link between variants of FGF21 and the desire for sweets.

To do so, they conducted two related studies. In the first, they used data from the Inter99 study, a genetic association study of thousands of Danish people between the ages of 30 and 60. Participants in the Inter99 study had blood drawn and answered a 198-question food frequency survey.

The researchers genotyped variants of FGF21 in the Inter99 study participants. They then compared how the hormone variations affected sweet food consumption.

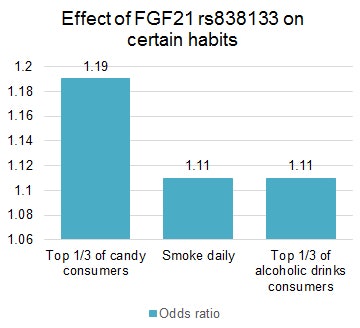

One FGF21 variation, the rs838133 A-allele, was significantly associated with increased sweet and candy consumption. Those with the variation had 19% greater odds of being in the top one-third of candy consumers, as the odds ratio graph above shows. An odds ratio represents the odds than an outcome will occur given a particular exposure.

"The takeaway is that there are likely to be genetic [and] endocrine mechanisms that control sugar appetite in humans," Gillum said.

People with this variation also had a significantly higher prevalence of smoking and alcohol consumption. However, they did not consume more calories, offsetting an increase in sugar consumption with a decrease in protein and fat consumption.

Surprisingly, despite consuming more sugar, those with the variation also tended to have better glycemic control, and researchers found no association with type 2 diabetes. People with the variant also had lower body mass indexes (BMIs) and waist circumferences than the average population.

"We are not totally sure about that yet. Though, it is important to note the variant confers a +3 gram of sugar effect per day, +6 if you have two copies of the variant, which is not a huge amount in an absolute sense," Gillum said. "We also saw that the subjects substituted sugar for other foods, so their overall calorie intake was unchanged."

FGF21 as a sweet regulator

For the second study, the researchers conducted a clinical trial with 51 healthy men and women between the ages of 18 and 39 who had a normal BMI. They wanted to see how fasting levels of FGF21 in the blood stream affected preference for sweet-tasting food.

The researchers found an inverse relationship between FGF21 levels and a preference for sweet snacks. Participants who did not like sweet snacks had a 51% higher concentration of FGF21 in their bloodstream than those who liked sweet snacks.

The researchers then invited 41 of the participants back for a longer observational period, which included 12 hours of fasting followed by consuming 75 grams of sucrose. After consuming the sucrose, FGF21 levels drastically increased for both the sweet-liking and sweet-disliking groups, suggesting that the hormone helps regulate sweet consumption.

"We were surprised that the human data was so supportive of our previous rodent work," Gillum said. “Not infrequently these lower organism findings don’t translate to humans!”

What other dietary effects does FGF21 have?

The researchers noted one major limitation of their studies: They relied on participants to self-report their preference for sweets. Thus, the researchers did not concretely demonstrate that FGF21 regulates sweet consumption, which they hope to do in future studies.

They also didn’t have dental diseases, such as caries, in mind when they conducted the studies. However, Gillum thought that FGF21 could have positive implications for oral health, although he noted that it would depend on the magnitude of the effect.

The researchers hope that future trials will look into the link between FGF21 variations and alcohol consumption. In the meantime, Gillum plans to conduct more human trials, which may lead to new methods to help change and regulate sugar consumption.

"We’d like to do a clinical trial in humans using FGF21 to look at sugar intake and also carry on looking for more genetic variants that are associated with food preference," he said.