A fake tongue, or chemical sensor array, was able to identify dental plaque from saliva samples but it could determine whether it came from a person with tooth decay and destroy it. The new research was published on February 25 in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.

Additionally, this discovery may help diagnose and treat bacterial dental diseases more quickly and cheaply in the future, the authors wrote.

Globally, bacterial infections account for 1 in 8 deaths and are the cause of dental diseases like caries, periodontitis, and peri-implantitis, which can have devastating effects on one’s health and quality of life in addition to other impacts.

Currently, identifying bacterial strains that cause a specific dental disease entail performing a culture or looking for a specific DNA marker using expensive equipment. These methods can take time and be costly.

To find a faster, more affordable way of identifying specific oral bacterial strains, researchers, led by Na Lu, a professorat the Shanghai University of Engineering Science in China, tested the accuracy and effectiveness of the artificial tongue.

The team used a nanoscopic particle that mimics natural enzymes -- a nanoenzyme -- made from iron oxide particles that were then coated in DNA strands. When hydrogen peroxide and a colorless substance were added to a solution to mimic saliva, the nanozymes turned bright blue. But bacteria that stuck to the DNA reduced the blue hue of the solution.

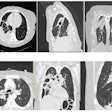

Next, the team coated nanozymes with different DNA strands, which when tested, resulted in unique color changes. From there, the researchers created 11 dental bacteria species. The artificial tongue identified all of the bacteria correctly in the artificial saliva samples. Moreover, using the nanozyme sensor, researchers could ascertain whether a dental plaque sample came from a healthy volunteer or one with dental caries.

Furthermore, the sensor had antibacterial effects on some of the samples. Of the 11 bacterial species tested, three were inactivated, and electronic microscope images revealed the sensor system destroyed the membranes of the bacteria. Though more research is needed, Lu et al believe the sensor could be used to diagnose and more quickly treat dental diseases at earlier stages, which could prevent severe progression and the associated complications of certain chronic dental diseases.

“Encouragingly, we envisage that this work can open up a new avenue for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of tenacious infectious diseases,” they wrote.