Fossil teeth can be used to calculate when a Neanderthal baby was weaned using a new technique developed to study teeth from human infants and monkeys (Nature, May 22, 2013).

Using the technique, the international research team concluded that at least one Neanderthal baby was weaned at much the same age as most modern humans.

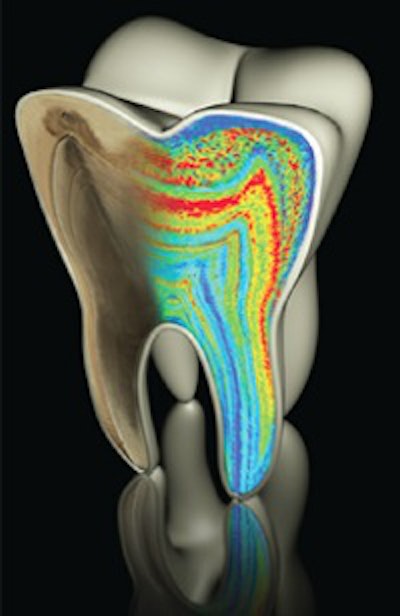

Molar tooth model shows color-coded barium patterns merging with a microscopic map of growth lines. Image courtesy of UCD.

Molar tooth model shows color-coded barium patterns merging with a microscopic map of growth lines. Image courtesy of UCD.The discovery is based in part on knowledge gained from infant and monkey teeth studies at the California National Primate Research Center at the University of California, Davis (UCD).

Just as tree rings record the environment in which a tree grew, traces of barium in the layers of a primate tooth can tell the story of when an infant was exclusively milk-fed, when supplemental food began, and at what age the infant was weaned, according to Katie Hinde, PhD, a professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University and an affiliate scientist at the UCD primate center.

Hinde directs the Comparative Lactation Laboratory at Harvard and has conducted a three-year study of lactation, weaning, and behavior among rhesus macaques at UCD. From mineral traces in teeth, the team was able to determine the exact timing of birth, when the infant was fed exclusively on the mother's milk, and the weaning process. By studying monkey teeth and comparing them with center records, they showed that the technique was accurate almost to the day.

After validating the technique with monkeys, the scientists applied it to human teeth and a Neanderthal tooth. They found that the Neanderthal baby was fed exclusively on the mother's milk for seven months, followed by seven months of supplementation -- a similar pattern to present-day humans. The technique opens up opportunities to further investigate lactation history in fossils and museum collections of primate teeth.

Although there is some variation among human cultures, the accelerated transition to foods other than breast milk is thought to have emerged in our ancestral history due, in part, to more cooperative infant care and access to a more nutritious diet, Hinde said. Shorter lactation periods could mean shorter gaps between pregnancies and a higher rate of reproduction. However, there has been much debate about when our ancestors began accelerated weaning.

For the past few decades, researchers have relied on tooth eruption age as a direct proxy for weaning age. Yet recent investigations of wild chimpanzees have shown that the first molar eruption occurs toward the end of weaning.